“I began to see art not primarily as an individual expression of talent, but as a responsibility, to reflect the spirit and style of the Negro people. It became an awesome responsibility to me.” John Biggers, quoted by Olive Jensen Theisen in, A Life on Paper: The Drawings and Lithographs of John Thomas Biggers (University of North Texas Press, 2006), p. 13.

Dr. John Thomas Biggers, Ph.D. (1924-2001) was keenly aware of the potential possessed by works of art to become forceful vehicles of self-identity. Through the scale and size of his murals, Biggers attempted to express the cultural heritage and identity of the people of his community. He sought to create a visual statement to bring about a spiritual encounter for all those who saw it. To Biggers, only the mural with its characteristic vastness in scope and scale could adequately accommodate the myriad visions which he wished to share with the people of his community.

Dr. John Thomas Biggers, Ph.D. (1924-2001) was keenly aware of the potential possessed by works of art to become forceful vehicles of self-identity. Through the scale and size of his murals, Biggers attempted to express the cultural heritage and identity of the people of his community. He sought to create a visual statement to bring about a spiritual encounter for all those who saw it. To Biggers, only the mural with its characteristic vastness in scope and scale could adequately accommodate the myriad visions which he wished to share with the people of his community.

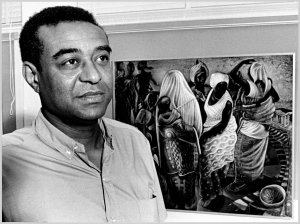

Born in Gastonia, North Carolina, on April 13, 1924, John Biggers was the last of seven children. When John Biggers arrived on the campus of Virginia's Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in the fall of 1941 his goal was to become a plumber. During his freshman year at Hampton, however, Biggers enrolled in an art class taught by the dynamic educator Viktor Lowenfeld. It was a course that changed his life. Lowenfeld encouraged his students to explore the culture of their own people. When Lowenfeld left Hampton for Pennsylvania State University, he encouraged Biggers to follow him. There he earned the bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate degrees. Biggers received a doctoral degree in 1954 with a thesis entitled The Negro Woman in American Life and Education. He established and chaired for 34 years the Department of Art at Texas Southern University in Houston, before retiring in 1983. In 1988, he was recognized as the Texas Artist of the Year.

Born in Gastonia, North Carolina, on April 13, 1924, John Biggers was the last of seven children. When John Biggers arrived on the campus of Virginia's Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in the fall of 1941 his goal was to become a plumber. During his freshman year at Hampton, however, Biggers enrolled in an art class taught by the dynamic educator Viktor Lowenfeld. It was a course that changed his life. Lowenfeld encouraged his students to explore the culture of their own people. When Lowenfeld left Hampton for Pennsylvania State University, he encouraged Biggers to follow him. There he earned the bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate degrees. Biggers received a doctoral degree in 1954 with a thesis entitled The Negro Woman in American Life and Education. He established and chaired for 34 years the Department of Art at Texas Southern University in Houston, before retiring in 1983. In 1988, he was recognized as the Texas Artist of the Year.

While working full-time as a teacher and administrator at Texas Southern, Biggers began establishing his reputation as a major African-American artist of the Southwest. From 1950 to 1956 Biggers painted four murals in African-American communities in Texas, which was the beginning of his interest in this category of painting.

One of these murals was a 1954 commission in honor of Professor Phineas Y. Gray (1886-1976) of George Washington Carver Negro High School. Dr. Biggers gave his creation the title, “History of Negro Education in Morris County, Texas.” The mural portrays the artist’s view in the 1950s of education for African American children in rural northeast Texas. As Biggers wrote in his doctoral dissertation, he wanted his viewers to identify themselves, and reflect on their own background and cultural heritage.

This project would not be possible without out the support of The Burt and Nancy Marans Charitable Fund at the East Texas Communities Foundation.

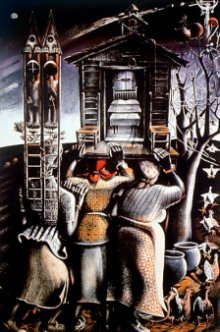

This great work of art is on a single bolt of muslin, 22 feet long and 6 feet tall. It is thinly painted in an oil-like medium on a heavily artist-primed muslin canvas. The painting is executed in thin washes of color similar to fresco technique. Biggers style is somewhat in the tradition of Thomas Hart Benton. His realistic images are big and powerful, and they communicate the facts of threadbare lives. The history of the mural, and the story it tells are fascinating.

In 1953-54, the Naples school board in rural northeast Texas sought to honor Mr. P. Y. Gray. He was retiring after nearly 30 years in the district. In 1929 he had been the first fulltime teacher at the Morris County Training School, and in 1954 he was principal of the newly completed George Washington Carver High School for Negroes. According to Dr. Olive Jensen Theisen, Ph.D., a noted John Biggers author, Mr. Gray suggested that a mural should be painted. The theme would be drawn from his Master's thesis at Prairie View A&M on the history of African American education in that county. School Superintendent Frank C. Bean commissioned Dr. John Biggers to paint the mural.

After investigating Gray’s contribution to the Morris County schools and after interviewing Bean and Gray, Dr. Biggers returned to Houston and went to work. In 1955 Biggers completed the long muslin painting and rolled it up to carry on the train to Naples. There it was quickly stretched on a wooden frame and installed in the library of the new Carver High School. The unveiling came on Sunday, March 20, 1955.

It hung in the High School for about fifteen years. By 1970 Integration and economic growth had come to northeast Texas. A new high school was to be built and Carver was converted to the Paul Pewitt Elementary School. The ceilings were lowered to accommodate younger children, and the mural no longer fit the available space. Probably because of its size, and the strong story, the Biggers mural went into storage under the band hall. After several moves over the years it ended up in an audio visual shed.

Dr. Jensen Theisen recalled that in the late 1970's, the students who had attended Carver High School in the mid-1950’s and were now adults and parents were curious about what had become of their mural. It was found it in the shed in remarkably good condition considering the climate. On Oct 27, 1989 Dr. Biggers attended a formal rededication of the mural in the Paul Pewitt Elementary School library. Prior to the ceremony, he repainted several damaged spots and supervised the installation of new frame that had been constructed by Dr. Jensen Theisen’s husband. The mural was finally returned to the library.

In collaboration with Northeast Texas Community College and the school district, the mural was removed from the elementary school library and taken to Dallas for much needed conservation in Helen Houp’s studio. After this brief exhibition in Tyler for about a month, the mural will be installed in it new home at Northeast Texas Community College.

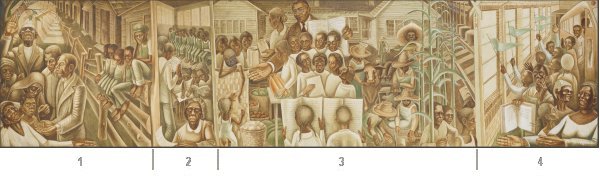

The four sections of the mural tell the story of the history of the progress of African American education in Northeast Texas. The first segment depicts the bleak period following the Civil War. The preacher is both spiritual leader and teacher. He addresses his congregation in a farm yard against a backdrop of laborers’ shanties. There is no school building as no land is owned. Education of the young is only a hope for the future. Children work in the fields or sit aimlessly on the rail fence. The preacher is depicted as urging the people to give offerings to build a church and school to lead to a better future.

The second segment shows a barren one room school, with some children reading and the rest sitting on a bench. This was a time without teaching contracts, and often without paychecks. The dour expression on the matriarchal teacher's face is further explained by the harsh language of the report card she holds in her hand.

The third and most dominant panel focuses on the time and work of the well-loved Mr. P. Y. Gray. He came to the Naples community in Morris County in 1929; in 1932 he graduated the first high school student. Gray stands in front of a “Rosenwald School” wood frame building. This panel describes a period of self-sufficiency. Students are seen quilting, raising and preserving food, caring for animals, and reading under the guidance of Mr. Gray and his wife Lucinda. She taught homemaking as he taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and agriculture and introduced athletics. Biggers uses Gray, and his outstretched arms as a “tree of life.” As Dr. Jensen Theisen observes, the strong male figure reaches out with open hands, holding “seeds of hope.”

The final segment of the mural features the new George Washington Carver High School and a real school bus, replacing the old plywood box on a truck chassis. It marks the beginning of the Consolidated Independent School District. The neighboring communities of Omaha and Naples had created one school board which then began to pay the bills for both the African American and white schools within the district. The mood of this segment is one of celebration and hope. The language in the book held by a teacher concludes, “Education pays in terms of law abiding citizenship.”

At the 1989 re-dedication, Dr. Biggers commented, “This event marks for me the climax of my career. I need nothing else. I told a story with meaning for this community which you have kept alive all these years, this is why I paint. There is no greater satisfaction.”